In third grade Stephanie Bruce and I become good friends. On Sunday mornings we ride the Spirit Buss to Temple Baptist Church together. On the bus a teenage youth counselor who even in the eyes of 8 year olds is overly self-impressed, plays guitar while leading a sing-along of One Tin Soldier (The Theme from Billy Jack), It’s Time to Rise and Shine and Give God Your Glory Glory Children of the Lord, This Little Light of Mine, We Shall Overcome, If I Had a Hammer, and inexplicably Puff the Magic Dragon. It is the thick of the seventies.

Every Sunday, they usher us into the children’s chapel where we hear a lengthy plea for tiny sinners to come forward and get born again. Then we attend the sort of Sunday school classes that I imagine Christians of all flavors attend: Bible story, Bible story-themed craft project, recitation of memorized Bible verses, bestowal of gold stars for well-memorized verses. Then back on the bus for another round of singing songs surely penned in a haze of marijuana.

I am told I was christened as an infant. As proof I offer a well-loved copy of A.A. Milne’s When We Were Very Young whose inscription is on the occasion of said christening. (My mother-in-law made certain my children were christened: I have Certificates of Baptism from the Church to prove it. Said certificates will be needed if my girls ever get married in the Catholic Church.)

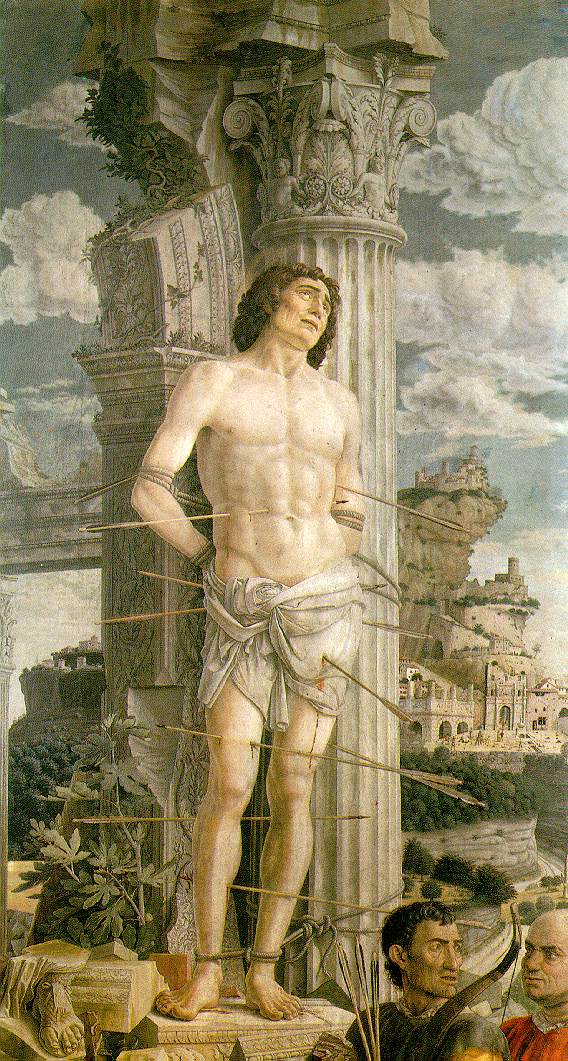

I am told I was christened as an infant. As proof I offer a well-loved copy of A.A. Milne’s When We Were Very Young whose inscription is on the occasion of said christening. (My mother-in-law made certain my children were christened: I have Certificates of Baptism from the Church to prove it. Said certificates will be needed if my girls ever get married in the Catholic Church.)Between my christening and third grade, God exists in my world as “God Talk” on Wednesday mornings at Trinity Episcopal Preschool and in Saturday morning broadcasts of Davey and Goliath. My parents do not talk about God. They talk about sunsets and wonder and goodness and peace. They quote the Bible, but do not read it. My sister and I are taken along on visits to art museums. My father uses Jansen’s Art History as our picture book as often as not, and through those discussions we hear Bible stories. My parents read and discuss Aesop’s Fables with us. Politeness, kindness, and compassion are emphasized.

One Sunday, I skip happily off the Spirit Buss to find my mother ironing in what was once the trunk room of our Victorian house. (It had become the kitchen for a second floor apartment prior to my parents buying the house and restoring it to a single family dwelling, so it had a counter cabinet with a sink and the rusted outlines of large appliances on the linoleum. Inside one of the cabinet drawers lay a package of rolling papers printed like draft cards and a long ribbon of sewing notion trim woven in an American flag pattern leftover from mom decorating one of my dad’s Levi jackets.) That Sunday, I had big news: I had been saved.

One Sunday, I skip happily off the Spirit Buss to find my mother ironing in what was once the trunk room of our Victorian house. (It had become the kitchen for a second floor apartment prior to my parents buying the house and restoring it to a single family dwelling, so it had a counter cabinet with a sink and the rusted outlines of large appliances on the linoleum. Inside one of the cabinet drawers lay a package of rolling papers printed like draft cards and a long ribbon of sewing notion trim woven in an American flag pattern leftover from mom decorating one of my dad’s Levi jackets.) That Sunday, I had big news: I had been saved.Without looking up from my father’s collar, my mother says, That’s great, Honey. Good for you.

I say, No, Mom, you don’t get it; I’m going to live forever in the house of the Lord and I will have His gifts visited upon me. (I like to imagine that I twirled my skirt with the gifts part, but I know I didn’t because I usually wore a pair of overalls with a large rose embroidered on the bib.)

Mom put down the iron and looked at my earnest face. I smiled waiting for a response. Mom picked the iron up and went back to work saying, You know, you don’t have to believe any of that crap.

And so began my relationship with organized religion.

Three decades later I am lying on my back, arms and legs akimbo for savasana. The instructor of the yoga class is doing that chatter that all yoga instructors do throughout class, but especially during savasana.

Savasana, or corpse pose is a relaxation posture usually assumed at the end of class. While meditative, it isn’t recommended for meditation because there’s a good chance you’ll fall asleep pumped full of endorphins and exhausted from an hour or more of sun salutations. Savasana is a post-coital experience. (Maybe it’s called “corpse pose” because it feels like you’ve just experienced the “little death”? I don’t know.)

One literalist instructor suggested imagining our flesh sinking into the earth, our presence retreating deep into our skulls to float in the eternal dark, our bodies rejoining the earth to become part of everything, as we always were part of everything. Imagine, she said, your flesh falling gently from your bones, your bones sifting away like powdery sands…

My moment comes with another instructor. (This particular instructor chattered less often than the corpse pose literalist.) This instructor says, breathe deeply-- enjoy the peace of this moment-- remember this peacefulness, the peacefulness of the contented infant-- it is the peacefulness we rose from and will return to-- it is the way we would be all the time, if we would only let ourselves.

And this is the closest I have ever been to God outside of the bedroom. (They don’t call it ecstasy for nothing.) It is my greatest chaste experience of the divine. It is in this moment that I realize, yes, the universe is a benevolent place and we are beloved of it.